MMFS is a laboratory for innovative teaching. Our teachers are constantly striving to implement the best research and methods to help students with language-based learning disabilities succeed. To introduce parents to the MMFS approach to teaching math, six lower school faculty members (Allie P, Gregg B, Divya S, Paula M, Henryetter S, and Franziska L) hosted a workshop explaining:

- how MMFS lower school teachers teach math;

- what gets in the way of math learning for students with learning disabilities; and

- what methods we use to engage students.

What does a learning disability in math look like?

What does a learning disability in math look like?

The workshop demystified for parents what constitutes a “Specific Learning Disability in Mathematics,” sometimes called “dyscalculia.” The teachers explained that it is characterized by “persistent difficulties in learning fundamental arithmetic facts, accurate, or fluent calculation, and/or accurate math reasoning. It is indicated by academic skills in mathematics that are significantly below the average range for individuals of the same age, education, and intellectual ability.” In other words, otherwise intelligent students who struggle to learn essential math facts, do age-appropriate calculations, or work on word/logic problems. The presenters also detailed how difficulties in math can be exacerbated by other learning disabilities. For instance, dyslexia can cause students to struggle to orient digits. Executive function problems can make it hard for students to lay out the steps in a multi-step problem.

A concept-first approach

A concept-first approach

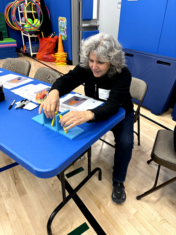

The workshop opened with a “Do Now” activity, mimicking for parents how this classroom activity transports students to “Mathland” (a great, self-explanatory term coined by a language therapist.) The grown-up attendees did a series of tasks on the concept of place value. They started with a Concrete activity, before moving to a Pictorial activity, and then an Abstract one. This follows the path that our teachers use to facilitate comprehension of an idea.

The workshop then moved to the benefits of the math curriculum we use, Math In Focus/Singapore Math. The core principle of this approach is teaching why a mathematical concept works before focusing on how to go about solving a problem. Put another way: We focus on the concept before we introduce the procedure. Teaching the procedure first, or over-emphasizing the procedure, can cause “cognitive interference.” This means students have difficulty understanding what a question is asking and how to solve the problem. Our students also learn multiple strategies for solving problems, which allows them to choose the most efficient approach. In addition, we encourage students to think in “math-ish” terms, i.e. to consider an estimation. All of these approaches boost students’ confidence in their abilities.

We teach this way because research shows that learning math facts by rote might help with solving a problem efficiently, but it does not always mean that a student understands the mathematical underpinning of the problem. For example: Memorizing 2 x 5 = 10 might not help you understand that 5 + 5 is the same thing. In addition, drilling math facts for fluency can lead to math anxiety, to which many readers can relate.

We teach this way because research shows that learning math facts by rote might help with solving a problem efficiently, but it does not always mean that a student understands the mathematical underpinning of the problem. For example: Memorizing 2 x 5 = 10 might not help you understand that 5 + 5 is the same thing. In addition, drilling math facts for fluency can lead to math anxiety, to which many readers can relate.

Supporting student learners outside the classroom

The workshop concluded with suggestions for ways that parents can reinforce math learning at home. Among the suggestions were playing math games and incorporating “Math Talk and Math Think” into household activities. But, they explained, students work hard in school, so math at home should be light and fun.

One reason that the MMFS math curriculum is so successful is the relationship among teachers, students, and families. The teachers at the presentation thanked the parents in attendance for their trust in them and for their participation in and commitment to helping their children feel successful in math.